The Compelling Case for Dictatorships (according to a guy I met)

Last week, I had a conversation that sent my brain spinning about how we decide which systems work, and which don’t.

The spinning began when our most recent Airbnb host here in Portugal (we’re working from here for a bit) mentioned in passing that authoritarian dictatorships are the best and most effective type of government.

“Democracy doesn’t work,” he told me in a throw-away fashion during our tour of the cottage, “everyone knows this.”

He went on to tell me how Antionio Salazar—the quasi-fascist leader of Portugal from 1932-1968—was the greatest thing that ever happened to his country.

For some context: During Salazar’s decades in power, Portugal had the lowest per capita income and the highest illiteracy rates in western Europe. He purposely kept the people uneducated to make it easier to maintain power, ended democratic elections, harshly oppressed dissidents, violently quelled freedom movements in Portugal’s colonies, and openly supported several of Europe’s fascists dictators—condemning their “morality” (Salazar was a devout Catholic) but not their facism.

Salazar also famously ruled with a hundred or so families whose interests, businesses, industries, etc. he protected and promoted.

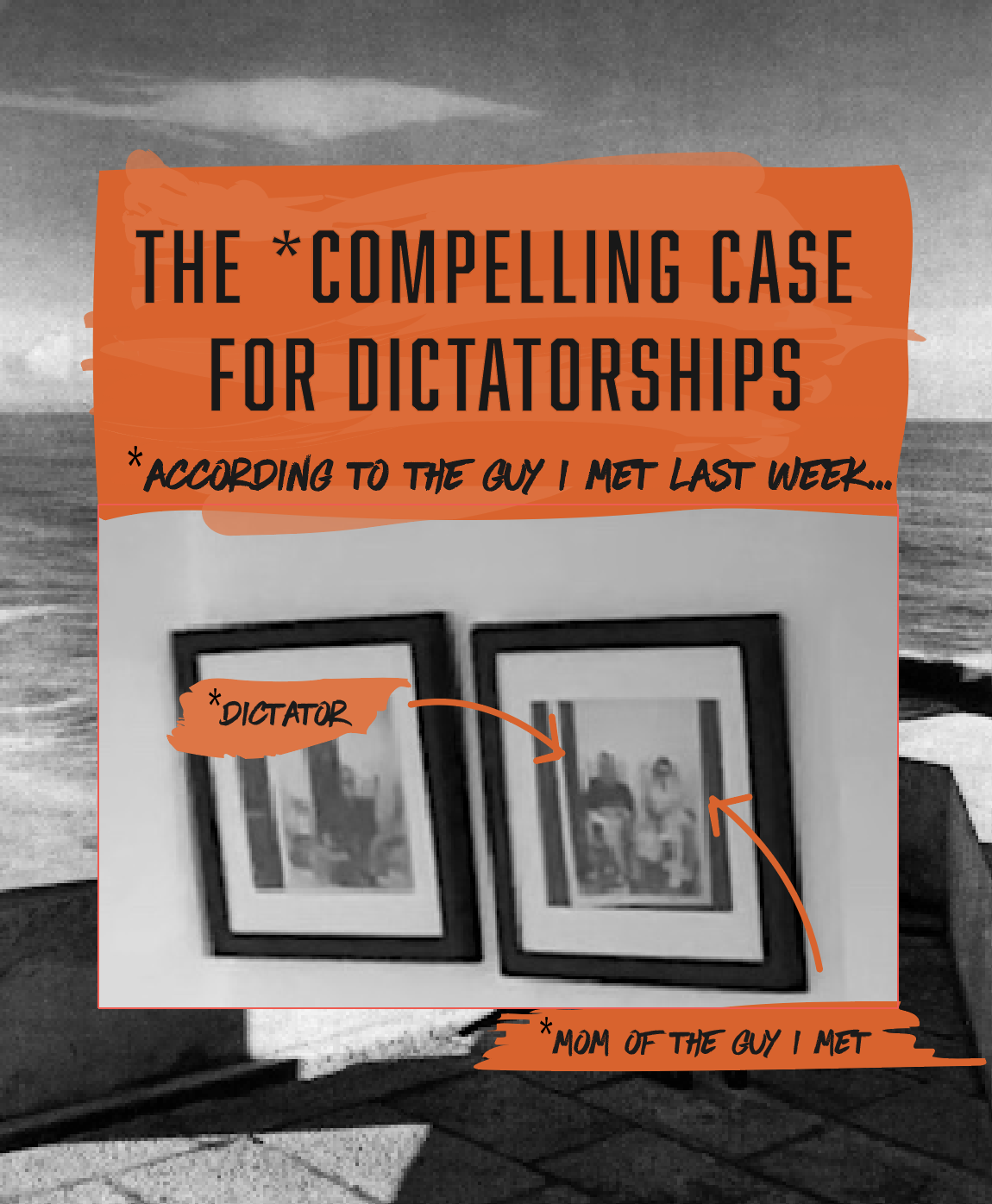

Uncoincidentally, our Airbnb host then took us around the kitchen table to proudly point out a collection of framed, black and white photographs showing his parents on holiday with Antonio Salazar (as well as one of the fascist kings of Italy). The photos are labeled 1941 and show happy, smiling people relaxing in front porch rocking chairs together. They were clearly close personal friends of Salazar’s and were doing just fine during his rule.

That when I realized… of course he believes that authoritarian dictatoriships are the best, most effective type of government. Because it was the best, most effective type of government for him and his family.

Now, I’ve lived long enough to realize that politcal leaders rarely fall neatly into “bad-guy” or “good-guy” narratives and Salazar is no exception—he has plenty of supporters and plenty of detractors and it’s undeniable that he did some good things for the country. But that’s not what this article is about.

My point is that our host’s statement was a perfect example of how we tend to universalize our experiences.

Authoritarian dictatorships must work… because it worked for me.

We do this all the time. For example:

American policing works because it works for me.

For-profit healthcare works because it works for me.

Sexist church policies work because they work for me.

Capitalism works because it works for me.

White feminism works because it works for me.

Our antiquated residential zoning laws work because they work for me.

Laissez faire climate policy works because it works for me.

Hardline immigration policy works because it works for me.

Anti-LGBTQ laws work because they work for me.

Abortion bans work because they work for me.

But if we only make and support systems that work for us (even if we are the majority) that doesn’t mean the system is good, or right, or even just. It simply means it works for us. Just like Salazar’s policies worked for our Airbnb host’s family.

Just like suffrage laws prior to the 15th ammendment worked for white men. Jim Crow worked for white people. Current tax laws work for the corporations benefiting from them and for the law makers whose campaigns they fund. Hell, even the policies of Nazi Germany “worked” for the majority of Germans. But I think we can all agree that those things didn’t and don’t actually work.

And, on the flipside, if a new policy comes along that still allows you to thrive, but perhaps you won’t make as much money because you’re no longer able to benefit at the expense of others, that doesn’t mean it’s not working.

Because good systems don’t work superbly well for a few at the expense of the rest. (Unless, you believe the ultimate indicator of a good system is the the ability of a few to become astromically rich off the labor of full time workers who earn so little they can’t feed their kids… in which case we need to have a different conversation.)

Good systems work well for everyone. They allow everyone to thrive. They make sure everyone has what they need, rather than making sure a few people have everything they want while the majority don’t even have what they need—enough food, clean water, a roof over their head, access to medical care, etc.

Which means generally speaking, our experience as an individual is not a good metric of what works. We must seek to understand and take into consideration not only what works for us but also what works for others. Listen, understand, and believe other people’s experiences and then create something that works for us as a whole.

And in order to do that, we have to first see ourselves as part of a collective. To see our wellbeing as tied up in the wellbeing of others. Interconnected enough that we could never do what our host did—look back in history to a time when we, as individuals, were thriving while everyone else was experiencing deep oppression, and say “those were the good ol’ days… let’s do that again.”

(Are we still talking about Portugal?)

We must go forward with imagination. Design and build new systems that work for everyone. Systems move us all toward justice, equality, and peace.

Can you picture it?